“I’m mad as hell and I’m not gonna take it anymore!” is the rallying cry at the end of the classic late 1970’s film Network. It signifies the implosion of the media industry’s inability to effectively channel rage in contemporary society. It’s also a call directed to no one. Instead of screaming into the pillow, the scream is made visible, people put their heads out the window and scream but they don’t have an addressee.

You might call this predicament — which I’d argue is emblematic of all modernity — to be stoic, as we are channeling our rage into consumerism, yoga, thrill sports, ecstatic encounters with nature, and the dimension of self that the Greeks called thymos remains largely neglected. Thymos is a type of innate recognition from others that grounds all human subjectivity.

One of the finest thinkers alive today, Peter Sloterdijk argues that rage remains a category of human desire that has suffered from a type of exclusion in the field of political thought and psychoanalysis, both to the detriment of social movements and the effective control of rage.

Sloterdijk’s Rage and Time: A Psychopolitical Investigation was initially of interest to me because of its critique of psychoanalysis, which I found to fall short of anything substantive, but I grew to find its real value in its positing of rage as a fundamental category of political thought. His argument is that rage is both implicit in western civilization historically and remains salient today in the so called “end of history” and post political deadlock, where rage remains non-institutionalized, and up for grabs. Governments, civil society, and reactionary movements have been unable to harness rage and have left open a field where alluring thymotic appeals to rage from Islamic extremist movements and left wing anarchial political movements become most visible.

Like happiness, rage lives in the present and has no temporality. Rage functions like a “bank” from where the subject deposits their rage into it and their bank is managed by a banker that takes the form of an ideology, or an individual, usually charismatic, what Sloterdijk refers to as an “entrepreneur of rage”. This bank asks that subjects situate themselves to a perspective and orient themselves to a history.

“Once the rage economy becomes elevated to the level of a bank, anarchistic companies led by small rage owners and locally organized anger groups become the subjects of harsh criticism” (Pg. 62).

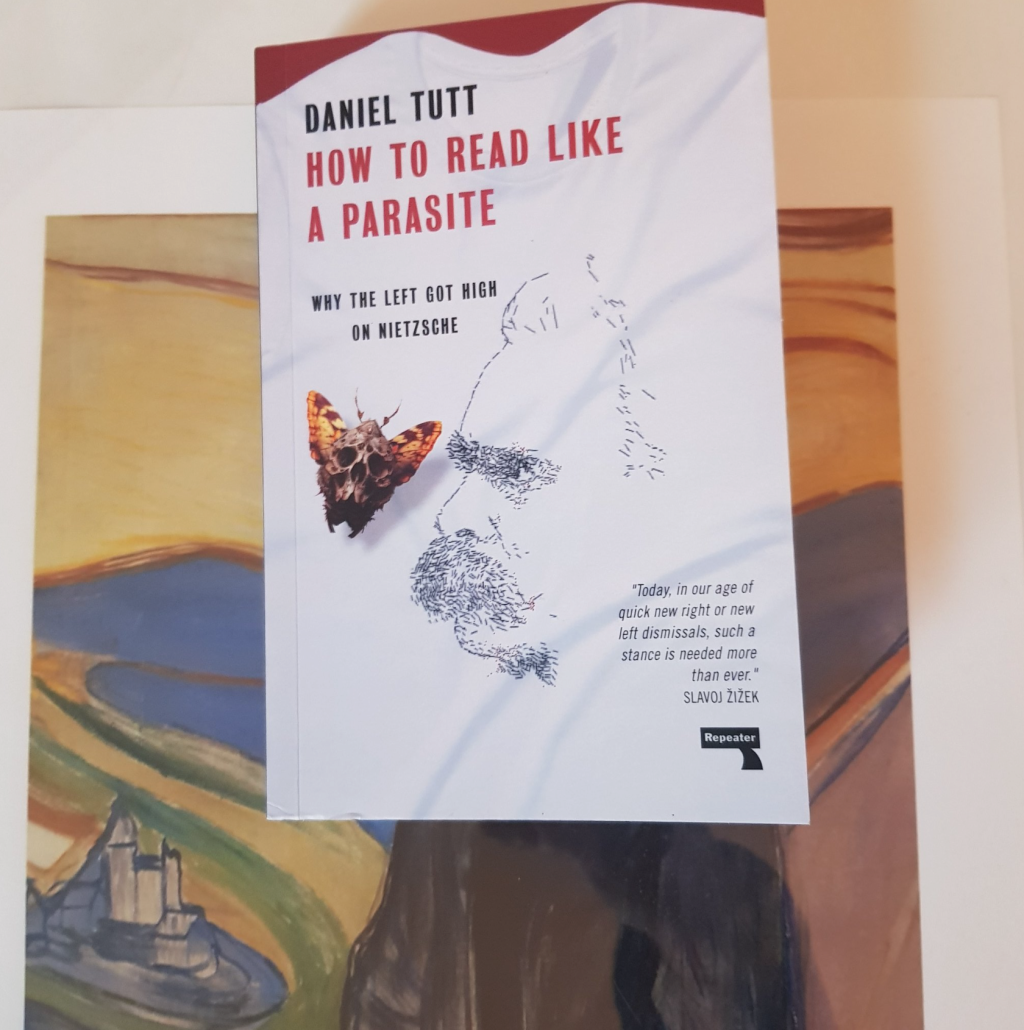

The decisive question in the present moment is whether it will be possible to invent new forms of productive rage that can do without a traditional addressee. The twentieth century experiments in rage resulted in genocide and wars, what Sloterdijk refers to as a “thymotic break of politics based on resentment.” Nietzsche insisted on the generalization of a latent resentment that projected the postponed wish for revenge onto its counterpart, the anxiety of being condemned as the basis of the Christian heritage in modernity. The Christian age was an age of deferring rage, not of practicing rage.

Equally critical of the left, Sloterdijk points out how the left has been overpowered by its own deception of everything as miserable. Even though he has been criticized for not giving a way forward out of the deadlock of thymotic politics, I gather from Sloterdijk’s text that we need new entreprenuers of rage and we need collectives that manage rage.

The depoliticization of civic life was of great concern following the “end of history” following the cold war to political theorists, but with the rise of Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, we’ve seen a return to singular demands that go beyond what philosopher Alain Badiou refers to as our deadlock, that between nihilism and democracy.

What might the next entrepreneur of rage look like? How might this entrepreneur go beyond the failures of a Lenin or a Trotsky in their logic of apocalypticsm that justified the wholesale elimination of those that were ideologically opposed to their politics? The left, unlike Christianity did not defer rage. In freeing themselves of their misery, what Hegel would call the negation of the negation of their humanity, the members of the Proletariat would storm the Bastille. Class consciousness has historically meant a consciousness of civil war, not the cultivation of one’s mind – this is crucial distinction, and one that must be revisited in today’s increasingly rage-prone political landscape.

As Sloterdijk points out, workers do not simply lose jobs any more. In a world guided by the ideal of the homo economicus, if you get fired you first lose your recognition as worker; if you lose your recognition as a worker, you lose your dignity; and if you lose your dignity, you lose your sense self. Under conditions of capitalism economic failure is moral failure.

Today, it appears that the only compelling rage entrepreneurs come from the right in the form of well amplified figures like Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh. Sloterdijk, himself a conservative philosopher notes that the left has since the French revolution, “engaged in a permanent war on two fronts: against happiness and against irony” (Pg. 118). They want to embody the rage of the world in a single person. Sloterdijk supports a well-managed rage thymotics of social rebellion that is structured under the hierarchy of a series of rage entrepreneurs. In short, while he is a conservative philosopher, I think that he is for leftist principles and yet unable to support the left because of their failure to implement a thymotic politics that is both compelling, structured and cultivating to the intellect.

This idea of the singular entrepreneur of rage has already proven to be nearly impossible in the Occupy Wall Street “leaderless revolution.” The problem in today’s world is that no one knows what to do with just anger, and we must face this deadlock from the crumbling welfare state, to international terrorism networks that have managed to cultivate excluded rage, to the neoliberal corporate consensus which is also failing in its management of rage. What lies ahead in the wholesale management of rage is yet to be seen, but I take my cue from Sloterdijk on the fundamental point that we need a strong thymotic critique and well positioned entrepreneurs of rage to lead us forward.

In a separate post and paper I am interested in looking at the potential failure of religious thymotics in sublimating rage and suppressing rage into a sort of Neitzschean resentment.

Leave a comment