Ibn Taymiyyah looms large in today’s imaginary; he is an untouchable authority in the minds of many Muslims. If you watch Salafi videos on YouTube, you’ll notice the hagiography around the man clouds many of his followers from engaging him on a serious or critical level. Some scholars are told to avoid him outright, while others say that he had a screw loose. He was known to have a bad temper and an erratic personality. But his legend is rightly deserved, for he defies the standard image of a quiet, contemplative scholar. He was a soldier, a jurist, and a philosopher; a sort of renaissance man who lived amid the brutal invasion of the Mongols during the late 13th century. He encouraged people to take up arms and fight, and he himself fought

I want to avoid the hagiography and mythicizing discourses around Ibn Taymiyyah and discuss his philosophical and theological ideas and how they pertain to politics. My premise here is that we can get a glimpse of the allure of what we today call political Islam, or Islamism by understanding the way in which Ibn Taymiyyah dealt with philosophical and theological debates, particularly his debates with the Ash’ari school.

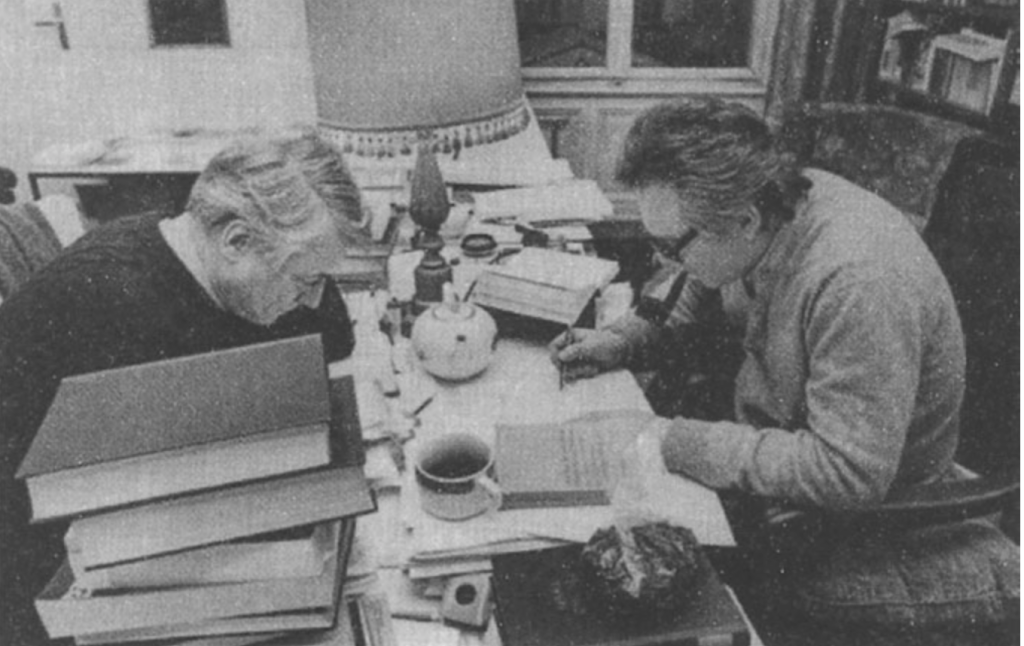

I have been reading three texts on Ibn Taymiyyah’s thought: John Hoover’s Ibn Taymiyya’s Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism, Wael Hallaq’s Ibn Taymiyya Against the Greek Logicians, and I finished a close reading of Ovamir Anjum’s book, The Taymiyyan Moment which was the focus of an excellent book club organized by my friends Mohammed and Rashid.

This post is an attempt to organize my own thoughts on Ibn Taymiyyah and I aim to expand on this and continue to read his work and the growing secondary literature on his work.

Ovamir Anjum starts his text with an analysis of how political authority in Islamic history has oscillated around two models of rule: a caliph centric and an ummah or community centric model. The history of Islamic political life, following the reign of the caliph Mu’awiyah, who many argue represents the end of the period of the rightly guided caliphs, is a story of decline in the community centric model of rule and the rise of a jurist class that increasingly excluded the masses of Muslims from political decisions as well as the way in which theology interacted with ethical life.

The Taymiyyan moment consists of this: the attempt to bring the position of the community centric model of rule back to the heart of Islamic political life. Moreover, the Taymiyyan moment is an attempt to empower Muslims in the domain of political agency. This political project of Ibn Taymiyyah, Anjum maintains, is grounded in philosophical and theological rebuking of the codified elitism found in the school of Ash’arism.

While Ibn Taymiyyah critiqued every school of thought, including the philosophers Ibn Sina and Ibn Arabi, the rationalists or the Mutazilites, and the Shi’ites, the most significant critique he wagered was against the Ash’arites. The Ash’arite school had come to represent the very failure of the caliph-centric model of rule, a problem that was deeply tied into their core metaphysics, a metaphysics which Anjum claims promotes a ‘fatalist voluntarism’ that places God’s will outside of ethics and morality.

The crux of Ibn Taymiyyah’s debate with the Ash’ari’s is around the proof of God’s existence. The Ash’ari school argued that God is not of temporality, his existence is not born in time like that of a body. As such, how does one arrive at a proof of God’s existence? It actually requires speculative reflection and the refinement of nazar or an advanced type of reasoning available only to scholars.

In the Ash’ari way of formulating the question of God’s existence, the entire problem became an exercise reserved for scholars alone, or those who have mastered reasoning. It is worth noting that the two major scholars of the Ash’ari school Fakhr al-Din al-Razi and Imam al-Ghazali, by the end of their lives openly argued against everyday Muslims engaging in the science of kalam or theology. This elitism is a natural offshoot, not of their flirtations with sufism and mystical quietism as much as it is with the very core of the voluntarist and fatalist metaphysics of Ash’arism. We should further note the timeliness of this debate between the Ash’ari’s and Ibn Taymiyyah and the way that it mirrors much of the debate Salafi’s have today with the system of taqlid, or blind following of a madhab or an Imam without effectively questioning that authority for oneself.

In addition to his critique of Ash’arism, Ibn Taymiyyah laid into the philosophers, mainly Ibn Sina, who put forward an argument for God’s existence that claimed God exists as al wujud al mutlaq – as absolute existence. To arrive at this absolute existence of God one must posses haqiqa or wisdom, but once again, this limits how one knows God to the mind alone and to the elite possession of a form of wisdom only the philosopher or jurist is able to obtain. Ibn Taymiyyah argued that individuals are so distinct and different from one another that they cannot form a universal across their minds or with haqiqa. An essence has no existence other than in the mind, leading Ibn Taymiyyah to adopt what Hallaq calls a ‘nominalist realism’. To define God as the necessary existent forecloses God from cause and effect, and like the Ash’ari’s who posit a voluntarist God outside of time, the philosophers had obscuratinized God and falsely assumed that ascertaining his existence through haqiqa would allow for the development of a shared universal truth, when the mind is incapable of producing universals. The philosophers had created a situation that blocked the common believer from possessing knowledge of God and his existence, for he could not attain proper ilm or knowledge, without possessing haqiqa. Ibn Taymiyyah’s argued that the greater the need a people has to know a truth, the easier God makes it for the intellects of the people to know its proofs.

But more politically important than the question of God’s existence is the way in which the Ash’ari ethical vision argued that political acts have no essential ethical value, but only acquire value upon divine command. Ultimately, good and bad can only be ascertained via revelation. Ibn Taymiyyah posits what Anjum calls “a moderate voluntarism” which accepted the view of the Ashari’s that good and evil are contingent while also accepting the Mutazalia view that unaided reason has the capacity to ethical verities.

The most important concept, indeed the secret way to understand Ibn Taymiyyah’s allure and radical vision and response to the philosophers, the Ashari’s and the rationalists is found in how he theorizes the concept of fitra, or natural reasoning. Fitra, according to Wael Hallaq is defined as:

“The faculty of natural intelligence, or the innate faculty of perception which stands in contrast to the acquired methods of reasoning that bring about perceptions in our mind” (Hallaq 55 Against the Greek Logicians).

Fitna is God’s way to make reason incline towards truth; it is thus an inborn type of knowledge that requires no reason to possess. Fitra is the foundation of reason. It is that which contains the knowledge of the truth, and is ma’rifa or knowledge that has not been obtained, as opposed to obtained knowledge or ilm. The fitra has an urge both for goodness and for understanding tawhid, or the divine unity of God. This natural reason, as Anjum notes, “separates right reason from reason’s misguided uses. The knowledge of good and evil is not ascertained through reason but is in fact only accessible through revelation.” Fitra is both the way that a common Muslim grasps revelation, and it is the foundation of ethical judgment that enables Ibn Taymiyyah to arrive at a reason-based approach to good and evil. Where the philosophers claimed haqiqa brought about the universal, fitra is what truly turns the believer towards universals because it is based on a predisposition to the good. This means that the good is located in the self, making the good ascertainable through subjective empiricism. Ibn Taymiyyah is more David Hume than Kant.

Ibn Taymiyyah is a deeply philosophical thinker, defying all conventions, as I have briefly outlined. But in his main political text, Siyasa al-Shariah he was concerned with politics being threatened by two sides: the tyranny of rulers who ignored the shari’a and mainstream jurists who neglected public welfare. But his argument was that it is the ummah, the community that must be the guardian of the shar’. This is specifically because the prophet is the last prophet, so the community can be trusted without an Imam to give it guidance. This makes his vision no longer that of a theocracy because it does not condone dictatorship.

Leave a comment